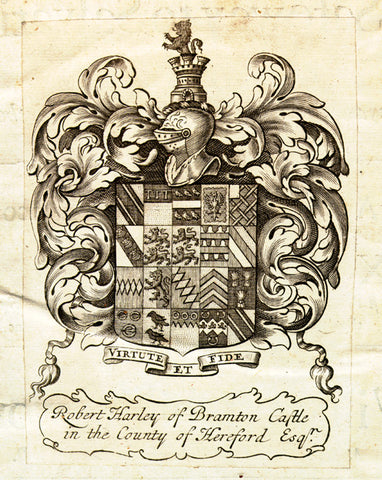

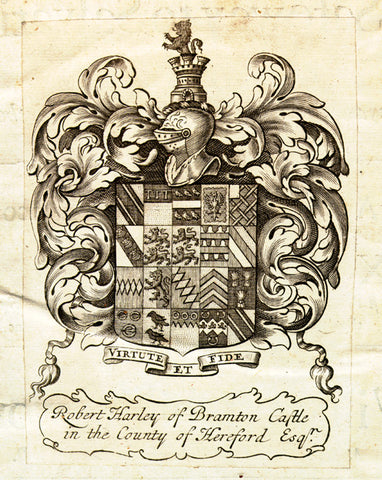

The practice of combining several Coats of Arms on one shield, known as “marshalling” arose from a desire to denote important marriage alliances. When a man married an heiress or co-heiress of an armorial family, he could incorporate her Arms permanently on his own shield, and transmit them to his descendents. He added not only her paternal Coat of Arms, but also any quarterings which may have accrued to it in the past. In this manner many present-day families carry in their Arms an heraldic record of a number of ancient families, their remote ancestors whose names have long since died out. An elaborately quartered shield is often far less artistic than a simple and less pretentious Coat of Arms; but it is historically of much greater interest, because it is an index to the former status and fortunes of the family that bears it.

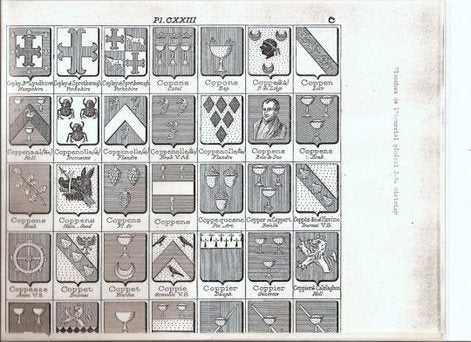

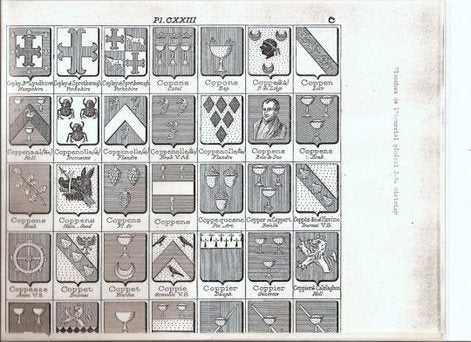

A good example of this method of Marshalling of Arms comes from the Arms of Gregory Fiennes, Lord Dacre of the South, who died in 1594. The Arms indicate that the members of the family of Fiennes had married the heiress of noble houses, whose ancestors had in their turn married other heiresses; so that Gregory bore beside his own paternal lions the Arms of Dacre, Multon, Vaux, Morville, Fitzhugh, Stavely, Furneaux, Grey, Marmion, St. Quentin and Gernegan. Lord Dacre had no children, but his noble display of Heraldry survives in the Arms of Emanuel School founded by his widow. The illustration of these Arms illustrate how metals and colors are denoted in heraldic drawings prior to the time when color was readily available for illustrative purposes. A plain surface represents white or silver ( Argent); dots represent gold (Or); vertical lines, red (Gules); horizontal lines, blue (Azure); diaginal lines, left to right downwards, green (Vert); and diagonal lines in the other direction, purple (purpure). This system of indicating colors and tinctures was not introduced until the seventeenth century and was widely used in Europe until the 20th century. One very notable use of this system was in Rietstaps Armorial General, an exhaustive index of over 50,000 European Arms.

Rietstap first published his Armorial général, contenant la description des armoiries des familles nobles et patriciennes de l'Europe, précédé d'un dictionnaire des termes du blason. This work contained the blazons of almost 50,000 noble families in Europe. They were all organized alphabetically by surname. He made extensive use of heraldic sources in a variety of languages to compile the Armorial. As word spread of the publication, he made more heraldic contacts around Europe and was able to expand the work to two volumes in 1884 and 1887.In 1871, European interest in heraldry was growing, thanks in part to Rietstap's work. Capitalizing on this, he was able to begin publication of an heraldic magazine. Specifically, he hoped that the Heraldieke Bibliotheek (Heraldic Library) would expose Dutch readers to the wider heraldic world. In 1872, the he went to press with the subtitle "Magazine for Heraldry, Genealogy, Seals and Medals." The magazine would be published until 1882, and was mostly filled with articles written by Rietstap himself. In the 1880s Rietstap also published two studies of the genealogy and coats of arms of the Dutch nobility, the Wapenboek der Nederlandschen Adel (Armory of the Dutch Nobility) which became available between 1880 and 1887 and De Wapens van den Tegenwoordigen en den Vroegeren Nederlandschen Adel met Genealogische en Heraldische Aanteekeningen (The Arms of Present and Past Dutch Nobility with Genealogical and Heraldic Annotations) published in 1890. In the prologue of this work, Rietstap continued his critique of the development of spelling in the Dutch language and heraldic blazon.